July 16, 2024: Vienna (Our Jewish Heritage)

Today was the day we’d planned to see all the Jewish history/heritage stuff. First stop was the Stadttempel, the main synagogue of Vienna. We were really looking forward to this, since Stef had discovered some family history that linked her to this Shul. She has some information indicating that she is a descendent of Solomon Colme, a former “Life Rabbi” of the Stadttempel. We took a tour, led by a lovely young college student named Adele, from Galicia, who gave us and three other visitors a tour in English.

Adele gave us the history of the Jewish community in Vienna, beginning in the 12th Century, up to 1420, when the Jews were expelled or murdered at the orders of Duke Albert V. Jews returned to Vienna in the 16th and 17th Centuries, since the emperors needed their financial support during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). But they were confined to a ghetto in a flood-prone area north of the Danube canal. They were again expelled by Emperor Leopold I in 1669-70 (the former ghetto still bears the name “Leopoldstadt”). Shortly thereafter, some Jews were again allowed back to Vienna (circa 1683), since (this time) the Habsburgs needed the assistance of Jewish bankers to finance the wars with the Ottoman Turks. Jews were were hated and stigmatized for their financial activities, but they were precluded by law from engaging in any other form of livelihood.

Our guide informed us that, after the resolution of the Ottoman wars, the lives of Jews were still very restricted, e.g., having to live in a locked ghetto. And they were not allowed to have formal clergy; Rabbis had to be referred to as Predigers (“preachers”). Nor were they allowed to build free-standing houses of worship.

The Ashkenazi Stadttempel was built in the 1820s, but it had to keep a low profile, so as not to challenge governmental restrictions which persisted even after the Edict of Tolerance issued by Emperor Josef II in 1782. The Jews had to wait until the 19th Century, under the reign of Emperor Franz Josef, to receive full citizenship and religious and political rights.

In 1938, there were nearly 200,000 Jews living in Austria. Today, there are about 10,000.

After the tour, Stef attempted to contact the archivist of the Stadttempel, to clarify the history of her ancestor. We went around the back of the Shul to the Archivist’s office, and spoke to a representative on the intercom:

We were given an email address with which to try to make contact. Email already sent; we’ll see, I guess.

We then proceeded to the Judenplatz, where the Jewish community lived during the Middle Ages. It was the location of a synagogue that had been destroyed (what else is new?) due to ever-present antisemitism. Its foundations are preserved in the Judenplatz Museum (shown below are the women’s section on the right, the men’s on the left and the “bimah”, or pulpit, in the middle):

Outside the Judenplatz Museum is the Judenplatz Denkmal (the Holocaust Memorial), also known as the “nameless library”–the walls depict library shelves turned inside out. The spines of the books are facing inwards and are not visible.

We then proceeded to the Jüdisches Museum. On the way, we passed the Hoher Markt, where we saw an iconic Vienna sight, the Ankeruhr (“Anchor Clock”). This is a mosaic-decorated clock that spans two buildings. It was installed between 1911 and 1917, originally intended to be an advertisement for an insurance company:

We again went past St. Stephen’s cathedral (love its tiled roof):

on the way to the Judisches Museum. There we saw more historical and religious relics, including a plinth that had marked the boundary of the Leopoldstadt ghetto.

The Jüdisches Museum also contained an enormous collection of Judaica that had been accumulated by Max and Trude Berger (Holocaust survivors):

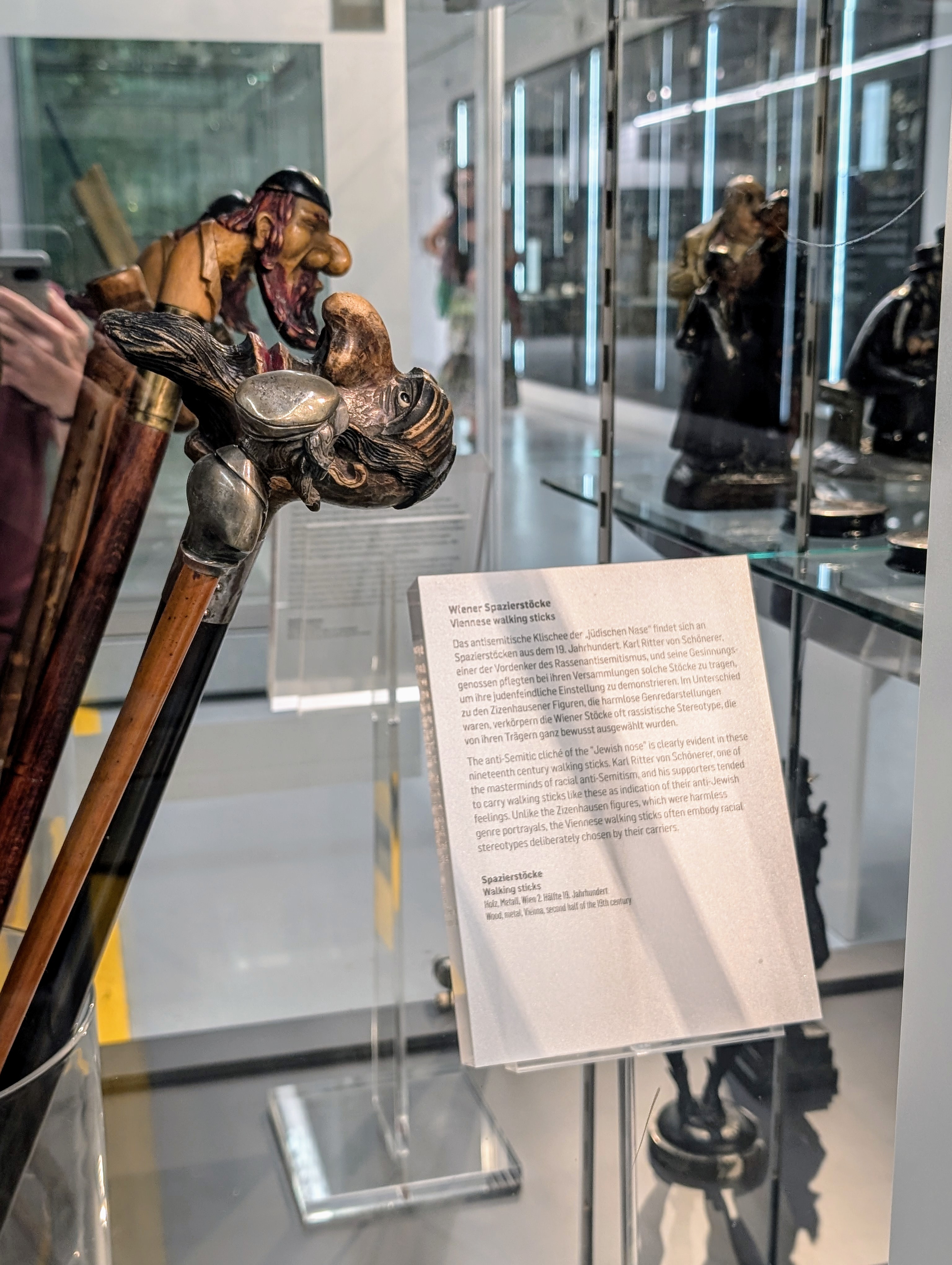

One of the exhibits featured walking sticks with antisemitic caricatures, whose proud owners maintained to show off their antisemitism:

Can you believe this? Who’d want to carry a cane with an image to display one’s bigotry? But, as someone has said, there are “fine people” on both sides of this issue.

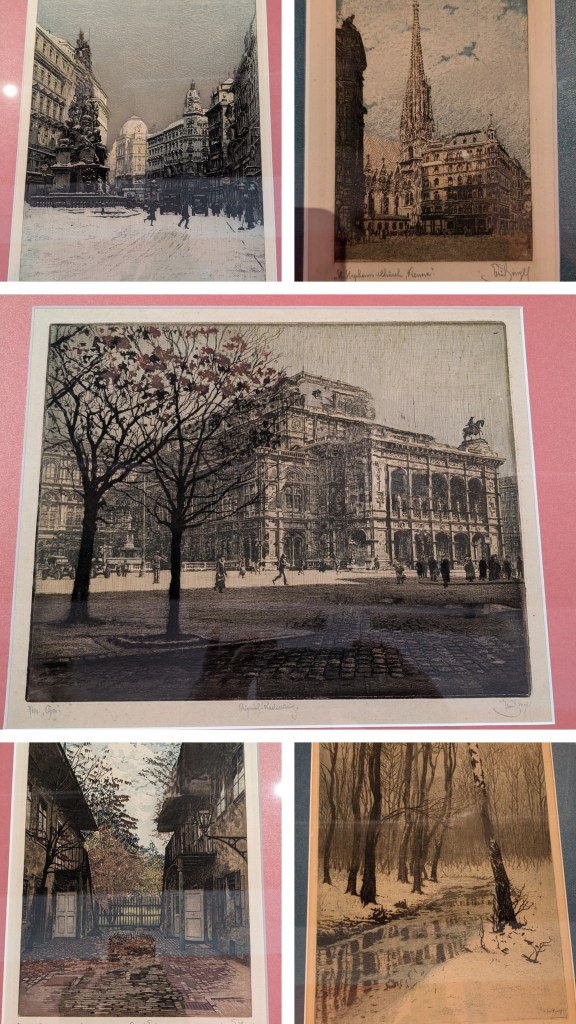

We ended our tour of the Jüdisches Museum with an exhibit of works by a Jewish illustrator, Emil Singer (no relation, as far as I know), who created etchings that captured lovely scenes of Vienna:

Emil eventually importuned friends in the U.S., to help him get out of Austria in the 1930s. No luck. He and his family were killed by the Nazis (sigh). In light of current events in the US, these memorials are especially relevant and troubling.

I promise that tomorrow will be a cheerier day.

Leave a comment